✝️ Medieval Art – From Stone to Light

1. Historical Context: Europe of Faith and Cathedrals

The Middle Ages (11th–15th century) was a period of intense creativity.

Far from the reductive image of “dark centuries,” it shaped the monuments that still define Europe’s towns and landscapes.

Two main forces animated this artistic impulse:

The monastic world: great abbeys (Cluny, Cîteaux) preserved knowledge, copied manuscripts, and organized liturgy. Their architecture inspired Romanesque art: sober, powerful, their churches became centers of pilgrimage, teaching, and spiritual radiance.

Urban and royal expansion: from the 12th century onward, cities grew, and royal dynasties such as the Capetians launched immense building projects. Cathedrals became both symbols of political prestige and sanctuaries of devotion. In this context, Gothic art flourished, fueled by urbanization and royal power.

Two styles dominated the era:

Romanesque art (11th–12th century): monumentality and stability.

Gothic art (12th–16th century): verticality, light, and daring technical innovation.

2. Philosophy and Worldview

Medieval art was a theology of stone and light.

The visible world was seen as the reflection of the invisible: every color, every proportion, every form carried spiritual meaning.

Romanesque: thick walls, semicircular arches, barrel vaults. These forms conveyed solidity, the eternity of faith, and the Church’s protective role. The Romanesque church was a spiritual fortress, reassuring and immutable.

Gothic: pointed arches, ribbed vaults, and flying buttresses freed the stone and opened interiors to light. Vertical thrust expressed the soul’s aspiration toward God, while stained glass transformed interiors into radiant clarity: light itself became divine message.

Sculptures, stained glass, illuminated manuscripts, and carved capitals formed a “Bible of stone and light”, meant to instruct the largely illiterate faithful. Nothing was merely decorative: gargoyles, roses, sculpted figures all carried symbolic or pedagogical meaning.

Thus, medieval art united the solemnity and mystery of Romanesque with the radiance and vertical impulse of Gothic, in a constant pursuit of spiritual elevation.

3. Aesthetics and Techniques

Romanesque Architecture

Characteristics: massive walls, small windows, semicircular arches, Latin-cross plans.

Atmosphere: penumbra, silence, stability, refuge.

Examples: Basilica of Saint-Sernin (Toulouse), Basilica of Sainte-Madeleine (Vézelay), Abbey of Cluny.

Gothic Architecture

Inventions: pointed arch, ribbed vaults, flying buttresses.

Effects: verticality, lightness, vast stained-glass walls.

Examples: Notre-Dame de Paris, Chartres, Reims, Amiens, Sainte-Chapelle.

Sculpture

Romanesque: capitals with biblical scenes, bestiaries, and moral symbols.

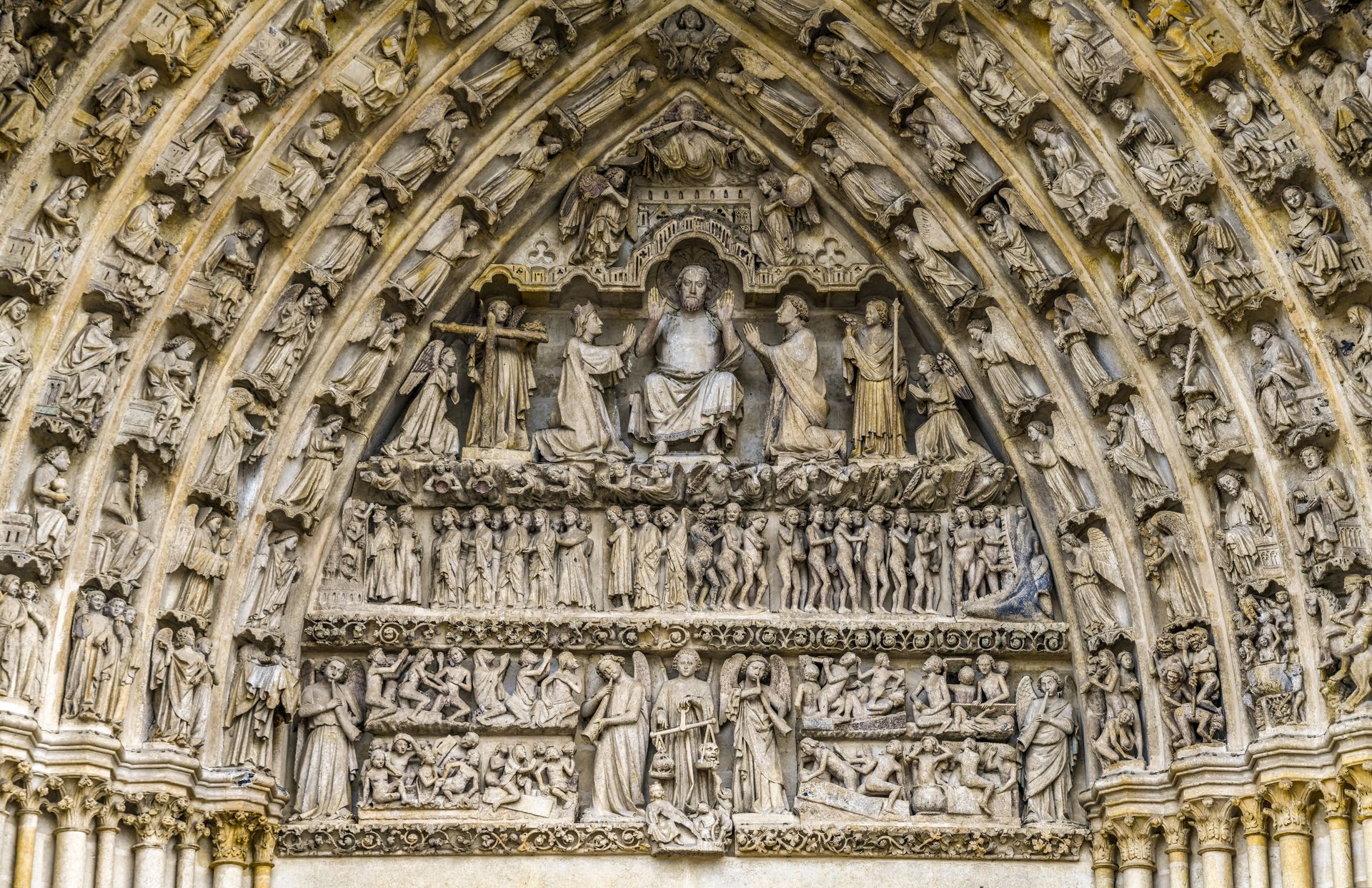

Gothic: portals filled with prophets, saints, angels, kings, and creatures. The column statues of Chartres or the Smiling Angel of Reims embody this new expressive power.

Stained Glass

True “Bibles of light”, teaching and astonishing the faithful. The Virgin of the Beautiful Window of Chartres is a celebrated masterpiece.

Illumination

Richly decorated manuscripts with gold, vibrant colors, refined miniatures. Famous examples: the Book of Kells(9th century) and the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry (15th century).

Painting

Wall frescoes (e.g. Saint-Savin-sur-Gartempe, the “Romanesque Sistine Chapel”).

Altarpieces and polyptychs (Maestà by Duccio, works by Cimabue, Giotto).

Icons and painted panels (Byzantine heritage, Italy and Eastern Europe).

Civic frescoes and early princely portraits at the end of the Middle Ages.

Decorative Arts

Goldsmithing: reliquaries, chalices, jeweled crosses.

Monumental tapestries (e.g. the Apocalypse Tapestry of Angers, 14th century).

Liturgical objects: monstrances, candlesticks, ivory and metal bindings.

4. Social Life and Symbolism

Medieval art was above all a collective art.

Cathedrals rose over generations, mobilizing master builders, stonecutters, sculptors, glassmakers, carpenters. These building sites became the living hearts of cities: each community competed to raise a monument expressing its faith and pride.

The cathedral was both house of God and house of the people: a place of prayer, gathering, festivity, and collective memory.

Its central symbols:

Stone: strength, stability, permanence.

Light: divine clarity, teaching for the simple.

Verticality: aspiration toward heaven.

Community: the artist effaced himself before the common work, a spiritual property of the entire city.

Stained glass, portals, tapestries, and manuscripts were at once instruments of teaching and meditation, as well as affirmations of prestige. Music — from Gregorian chant to the first organs — completed the experience: an art that enveloped sight, hearing, and soul.

5. Iconic Works

1. Mont-Saint-Michel (France, 11th–16th centuries)

A universal symbol, this masterpiece combines Romanesque abbey and Gothic additions. Rising on a rocky islet between sky and sea, it embodies the mystical power and spiritual elevation of medieval Europe.

2. Cologne Cathedral (Germany, begun in 1248)

A Gothic masterpiece of Central Europe, it impresses with spires reaching 157 meters, among the tallest in the world. Its sculpted façade and stained glass make it one of Europe’s most visited and recognizable churches.

3. Chartres Cathedral (France, 12th–13th centuries)

Famous for its unique blue stained glass and sculpted façade, it is the perfect symbol of Gothic as a “Bible in stone and light.” Its Virgin of the Beautiful Window remains one of the world’s most iconic stained-glass works.

4. Reims Cathedral (France, 13th century)

The coronation site of French kings, it is both a political and religious manifesto. Its Smiling Angel has become the emblem of a more expressive Gothic, where stone comes alive with grace.

5. Sainte-Chapelle, Paris (France, 13th century)

A jewel of radiant Gothic, where walls nearly vanish behind immense stained glass windows. Built to house relics of the Passion, it embodies the idea of an earthly paradise bathed in light.

6. Heritage and Posterity

Medieval art left a profound imprint on Europe.

Its cathedrals still dominate landscapes (Chartres, Paris, Cologne, Milan).

Its symbolic language — stone, light, verticality — remains at the heart of Europe’s imagination.

Its conception of art as a total and communal work anticipated the great artistic syntheses of modernity.

Gothic enjoyed a 19th-century revival (Viollet-le-Duc, Neo-Gothic), proof of its timeless power.

Today, this heritage continues to inspire literature, cinema, and video games, from fantasy to dark romanticism.

👉 More than a style, medieval art gave Europe a visual and spiritual soul of stone and light, one that continues to raise eyes and hearts toward the eternal.

7. Imperion – Heir to the Medieval

Imperion does not reproduce medieval art: it extends its spirit.

Our inspiration is not religious belief, but the power of symbols and the beauty of forms.

From the Romanesque, we retain quiet strength, solidity, and permanence.

From the Gothic, we retain vertical momentum, transfigured light, and the conviction that art can uplift and unite.

Like the medieval builders, Imperion believes in art as a collective and transcendent work.

Each creation becomes a stone in an invisible cathedral, a voice of beauty turned toward eternity.