🏛 Greco-Roman Art – The Roots of European Beauty

1. Historical Context: The Birth of an Ideal

Greco-Roman art is the backbone of Western visual culture. It took root in ancient Greece, flourished under the Roman Empire, and became the matrix of all European aesthetics.

Archaic Period (7th–6th century BC)

Greece created its first artistic canons: statues of kouroi and korai, temples with geometric lines. Forms were rigid, yet already animated by the search for order and proportion.

Classical Period (5th–4th century BC)

Athens, center of an artistic and intellectual revolution, placed art at the heart of the city and democracy. Under Pericles, the Parthenon embodied the union of mathematics and the sacred: a temple conceived as perfect architecture, both civic language and divine dwelling. Sculpture, theater, and urbanism expressed the quest for ideal harmony.

Hellenistic Period (4th–1st century BC)

After Alexander’s conquests, Greek art spread from the Near East to Egypt. More expressive and dramatic, it multiplied themes: heroes in motion, tormented faces, intense emotions. Aesthetics were no longer only about balance, but also theatricality and pathos.

Rome, Conqueror and Builder (1st century BC – 4th century AD)

Rome adopted the Greek heritage and raised it to an imperial scale. Temples, forums, triumphal arches, baths, and amphitheaters became instruments of political and universal art. Technique (arches, vaults, domes, concrete, aqueducts) fused with symbolism: art served to impress, glorify, and unify.

👉 Between the Greek quest for ideal perfection and the Roman mastery of universal construction, Greco-Roman art established itself as the cultural framework of Europe, an aesthetic and political language that continues to inspire civilizations.

2. Philosophy and Worldview

For the Greeks, beauty and truth were inseparable. Beauty was not mere ornament: it revealed a cosmic order.

Plato taught that beauty was the sensible reflection of the world of Ideas — a path of elevation toward the eternal. Art became a pedagogy of the soul.

Aristotle, more pragmatic, defined art as mimesis — imitation of nature, but ennobled and regulated by ideal proportion.

The concept of kalokagathia (union of the beautiful and the good) linked aesthetics, ethics, and civic life: the beauty of the body reflected a virtuous soul and a just city.

Yet Greek philosophy was diverse:

The Stoics (Zeno, Seneca, Marcus Aurelius) saw in cosmic harmony a rational order that art should express. Beauty resided in coherence with nature and reason.

The Epicureans (Epicurus, Lucretius) valued measured pleasure and wonder before the visible world: art could be a source of serenity and inner balance.

At Rome, art acquired a more political dimension:

It glorified rulers (realistic busts, heroic statues).

It immortalized victories (triumphal arches, commemorative columns).

It projected the Empire’s image (coins, official portraits).

👉 Greco-Roman art was thus at once a philosophy of beauty, a wisdom of life, and an instrument of memory and power.

3. Aesthetics and techniques

Greco-Roman art sought a balance between idealization and realism, between mathematical harmony and the vitality of the sensible world.

Sculpture

Stylistic evolution:

Archaic: kouroi (youths) and korai (maidens), rigid yet striving for proportion.

Classical: perfection of canons, balance and controlled movement (Discobolus by Myron, Doryphoros by Polykleitos).

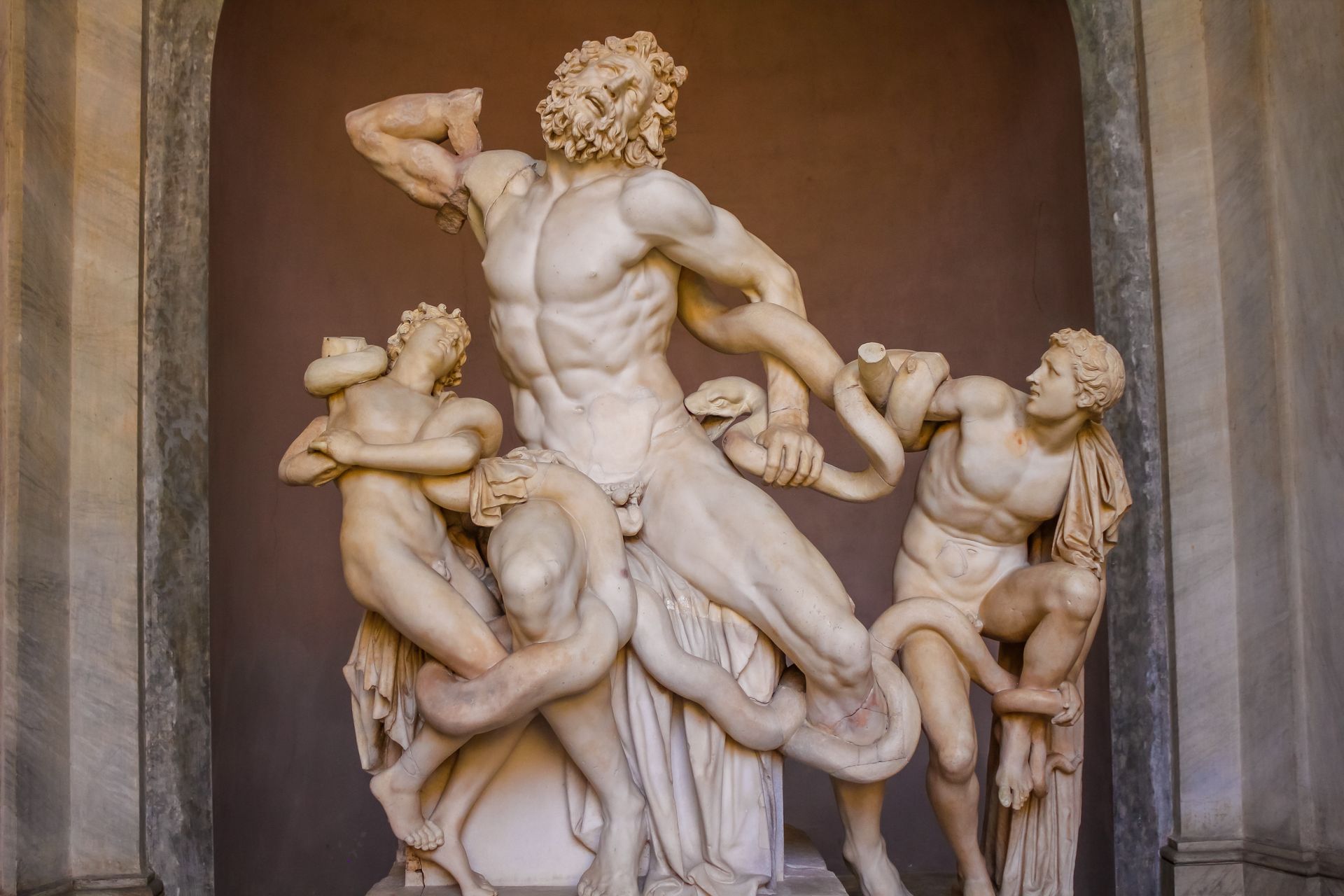

Hellenistic: expressiveness, dynamism, pathos (Laocoön, Winged Victory of Samothrace).

Materials: Parian and Pentelic marble, bronze for originals (often lost).

Polychromy: statues were painted, enhanced with gold and ivory (e.g. Phidias’ Athena Parthenos).

Roman realism: emperor busts and ancestral portraits (verism), highlighting wrinkles, scars, distinctive features → art as memory and political instrument.

Architecture

Greek orders:

Doric (strength, sobriety),

Ionic (elegance, refinement),

Corinthian (decorative richness, acanthus leaves).

Roman innovations: the arch, vault, dome, and above all concrete, enabling monumental structures.

Urban spaces:

Agora and forum as civic hearts.

Theaters and amphitheaters (Colosseum) for collective entertainment.

Baths combining architecture, hydraulic engineering, and decoration.

Masterpieces:

The Parthenon (Athens): ideal of proportion and purity.

The Pantheon (Rome): dome with oculus, technical and cosmic feat.

Decorative Arts and Visual Techniques

Mosaics: mythological scenes, gladiatorial combats, still lifes decorating villas and public places.

Frescoes: Pompeii and Herculaneum reveal refined domestic art with illusionistic perspective.

Goldsmithing: jewelry, precious tableware, liturgical and civic objects.

Coins: tools of propaganda, circulating the emperor’s portrait throughout the Empire — among the first mass media.

👉 Between the Greek search for ideal perfection and Roman pragmatism in construction and diffusion, Greco-Roman aesthetics embodied the union of beauty and power, thought and matter, heritage and innovation.

4. Social Life and Symbolism

Greco-Roman art was not reserved for elites: it permeated all public, religious, and political life. It was spectacle, cult, education, and propaganda.

Theater and Civic Education

In Greece, theater was a true school of citizenship. The tragedies of Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides taught justice, fate, and responsibility. The comedies of Aristophanes critiqued society and politics. Publicly funded, they were attended by all: popular art with a high moral function.

Games and Sport

Statues of athletes, gymnasiums, and stadiums celebrated the body as reflection of divine harmony. The Olympic Games, held in honor of Zeus, imposed a sacred truce, reminding Greeks that sport could unite rival cities in fraternity.

Religion and Cult

Temples, altars, and votive statues filled urban space. Art expressed piety and civic power: cities rivaled in magnificence through their sanctuaries. In Rome, temples to Jupiter, Mars, and Vesta confirmed the fusion of religion and politics.

Power and Propaganda

Rome turned art into a universal language of domination. Triumphal arches, commemorative columns, forums, and baths served as monuments of prestige and memory, impressing both citizens and conquered peoples. Domestic art (villa frescoes, mosaics) also spread an imagery of wealth and order.

The Symbol of the Laurel

The woven crown became the emblem of poets, generals, and emperors: a sign of victory, but also of public recognition. It embodied glory as both civic and spiritual value, uniting aesthetics and dignity.

👉 Greco-Roman art was more than ornament: it was a visual pedagogy, a tool of social cohesion, and an instrument of power, where every statue, mosaic, and theater expressed a shared worldview.

5. Iconic works

Greco-Roman art left us a constellation of works embodying its ideal of beauty, power, and harmony. Among them, several shine as eternal landmarks:

1. The Interior of the Pantheon, Rome (118–125 AD)

With its perfect dome of over 43 meters and central oculus, it unites technical mastery with spirituality. The light passing through the oculus, moving with the sun’s course, makes the Pantheon both cosmic clock and universal sanctuary.

2. The Discobolus of Myron (460–450 BC, Roman copy 2nd century AD)

A Roman copy of a lost Greek bronze, it captures the instant when the athlete prepares to throw his discus. Everything here is balance: the tension of muscles, the focus of the face, the suspended motion. A perfect image of the Greek pursuit of harmony between energy and grace.

3. The Pompeii Mosaic – Alexander the Great (c. 100 BC)

Discovered in the House of the Faun, this vast mosaic recounts the Battle of Issus against Darius. Its breathtaking detail shows how Roman decorative art could become heroic narrative, colorful and vibrant.

4. The Laocoön Group (c. 200 BC, rediscovered in 1506)

A Hellenistic masterpiece, it depicts the Trojan priest Laocoön and his sons entwined by sea serpents sent by the gods. The dramatic intensity, the torsion of bodies, the expression of suffering raised Greek art to its height of emotion and theatricality. A symbol of human struggle against fate, it contrasts with the serene ideal of the Discobolus and reveals another face of Antiquity: tragic grandeur.

5. The Bust of Augustus of Prima Porta (c. 20 BC)

An official portrait of Augustus, embodying imperial power and the role of art as political instrument. Through realism and idealization, Rome fixed an eternal image of its rulers.

6. Heritage and Legacy

Greco-Roman art has never ceased to inhabit Europe and the world.

Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages

After Rome’s fall, its forms survived in Early Christian and Byzantine art (Old St. Peter’s Basilica, Ravenna mosaics). Monasteries preserved Vitruvius’ treatises and ancient philosophy.

Renaissance

A conscious rediscovery: Brunelleschi drew on the Pantheon for Florence’s dome; Raphael and Michelangelo revived Greek and Roman canons; humanism enshrined Antiquity as the model of perfection.

Classicism and the Enlightenment

In the 17th–18th centuries, Greek and Roman art became a universal reference: Poussin and David in painting, Palladio and Soufflot in architecture. The classical orders (Doric, Ionic, Corinthian) remained central to academic vocabulary.

Neoclassicism and Modernity

From Paris to Berlin, London to St. Petersburg, capitals adopted colonnades and domes. In the United States, the Founding Fathers directly embraced Greco-Roman models to embody the republic (Capitol, White House, Jefferson Memorial).

Contemporary Posterity

Today, Antiquity remains the visual language of stability and greatness: museums, universities, parliaments, banks, and international institutions (UN, US Supreme Court) still employ colonnades and pediments as symbols of permanence and universality.

👉 More than a style, Greco-Roman art became a cultural matrix. It embodies the idea that beauty, when founded on harmony and measure, can traverse centuries and speak to all civilizations.

7. Imperion — Heir to Antiquity

Imperion does not reproduce Antiquity: it extends its soul.

The laurel, symbol of glory, has become the emblem of our house.

The harmony of proportions guides our vision of creation.

Our inspiration lies not in religious belief, but in the universal symbols Antiquity bequeathed: light, beauty, wisdom, vitality.

We draw upon its forms and timeless values to reinterpret them in contemporary creations.

Thus, each Imperion work, even when unique today, is conceived as a voice in dialogue with the gods, the empires, and eternity.