✨ Classical and Neoclassical Art – The Order of Reason

1. Historical Context: Europe of Measure and Clarity

In the 17th century, after the splendor and excess of Italian and Spanish Baroque, France imposed an aesthetic of order, clarity, and discipline: Classicism.

Under Louis XIV, art became an instrument of government. Versailles, designed by Le Vau, Hardouin-Mansart, and Le Brun, expressed the glory of the Sun King: official, rational, and regulated by the Academy and the rules of proportion.

Yet Classicism was not only French: in England, Christopher Wren built St. Paul’s Cathedral (1675–1710), a synthesis of Gothic tradition and Classical clarity; in Italy, Baroque sometimes shifted toward more ordered aesthetics (Guarini in Turin). Europe sought a stable language amid wars and religious upheaval.

In the 18th century, the rise of the Enlightenment radically transformed art’s role. Printing spread books and encyclopedias; academies, salons, and cafés became centers of debate. Art reached a wider audience and assumed an educational and civic function. Architecture favored clarity, science and geometry guided form.

From 1738 (Herculaneum) and especially 1748 (Pompeii), archaeological excavations revealed an intact ancient world. Piranesi’s engravings and Winckelmann’s writings (History of the Art of Antiquity, 1764) fueled a new passion: Antiquity was no longer just an aesthetic model, but a moral and political ideal.

In the late 18th century, this fascination gave rise to Neoclassicism. It accompanied the upheavals of the age: the French, American, and European Revolutions, then the Napoleonic Empire. Artists such as David and architects like Soufflot placed their art at the service of civic ideology. Antiquity became not decoration, but an example of virtue and public greatness.

👉 Thus, between monarchical Classicism, rationalist Enlightenment, and revolutionary Neoclassicism, Europe shaped an art that became at once language of power, pedagogical tool, and civic ideal.

2. Philosophy and worldview

Classical and Neoclassical art expressed a philosophical and moral reflection in which beauty was inseparable from truth and order.

Classicism

Inspired by Descartes (Discourse on Method, 1637), French thought prized clarity, symmetry, and rigor. Rule became the guarantor of truth.

Boileau (The Art of Poetry, 1674) fixed the Classical ideal: “Nothing is beautiful but the true; the true alone is lovable.” The tragedies of Racine or the canvases of Poussin embody this balance between reason, measure, and restrained emotion.

The Enlightenment

In the 18th century, art became a vehicle of knowledge and reform.

Diderot, in his Salons (1759–1781), invented modern art criticism: works must move and instruct.

Montesquieu and Voltaire connected aesthetics with political organization.

Rousseau reflected on education and the social role of the arts.

Thus, art was no longer for elites alone but a tool of collective progress.

Neoclassicism

Winckelmann (History of Ancient Art, 1764) defined Greek art’s ideal as “noble simplicity and quiet grandeur.”Beauty was moral; it uplifted the soul.

In David, art became civic: Roman heroes embodied virtue and sacrifice.

Finally, Kant, in the Critique of Judgment (1790), theorized aesthetic judgment as universal: beauty was not subjective but expressed a harmony every mind could recognize.

👉 From Descartes to Kant, from the Louvre to the Revolution, Classical and Neoclassical art united reason, beauty, and virtue into a universal language.

3. Aesthetics and Techniques

Architecture

Classicism (17th c.): order, symmetry, clarity. Façades followed strict hierarchy. The Colonnade of the Louvre(Claude Perrault) is its manifesto: majestic yet sober, Cartesian reason in stone. Versailles, with Le Nôtre’s geometric gardens, embodied the King’s absolute control over nature and space.

Neoclassicism (18th c.): a return to Antiquity’s pure forms, enriched by Pompeii and Herculaneum. The Panthéon in Paris (Soufflot) and the Brandenburg Gate (Langhans) conveyed austere monumentality and civic ideals. Visionary architects such as Boullée (Newton Cenotaph) and Ledoux (Salines of Arc-et-Senans) explored utopian, geometric, and symbolic architecture.

Painting

Classicism: drawing dominated color. Poussin codified the rules of history painting with clear compositions and moral themes. Le Brun used painting as royal propaganda at Versailles. Claude Lorrain exalted idealized landscapes bathed in golden light.

Neoclassicism: art became civic. David (The Oath of the Horatii, The Death of Marat) exalted republican virtues. Ingres pursued the ideal of pure line and perfect form. Mengs theorized noble, archaeological painting. Color was restrained; emphasis lay on drawing’s purity and heroic figures.

Sculpture

Classical France: measured, noble works for Versailles and royal gardens (Girardon, Coysevox).

Neoclassicism: polished marbles by Canova (Psyche Revived by Cupid’s Kiss, Pauline Borghese as Venus) or Thorvaldsen. Draperies were fluid, anatomies idealized. Sculpture translated Antiquity into modern symbols of virtue and heroism.

Decorative Arts

Classicism → refinement of Louis XIV and XV: controlled gilding, symmetrical décor.

Neoclassicism → Louis XVI and Empire furniture: straight lines, antique motifs (palmettes, eagles, laurels).

Sèvres porcelain, Wedgwood ceramics in England, imperial goldsmithing. Ornament was not mere luxury: it transmitted civic and moral symbols.

👉 Classical and Neoclassical art always sought to unite beauty and virtue, measure and exemplarity.

4. Social and Symbolic Life

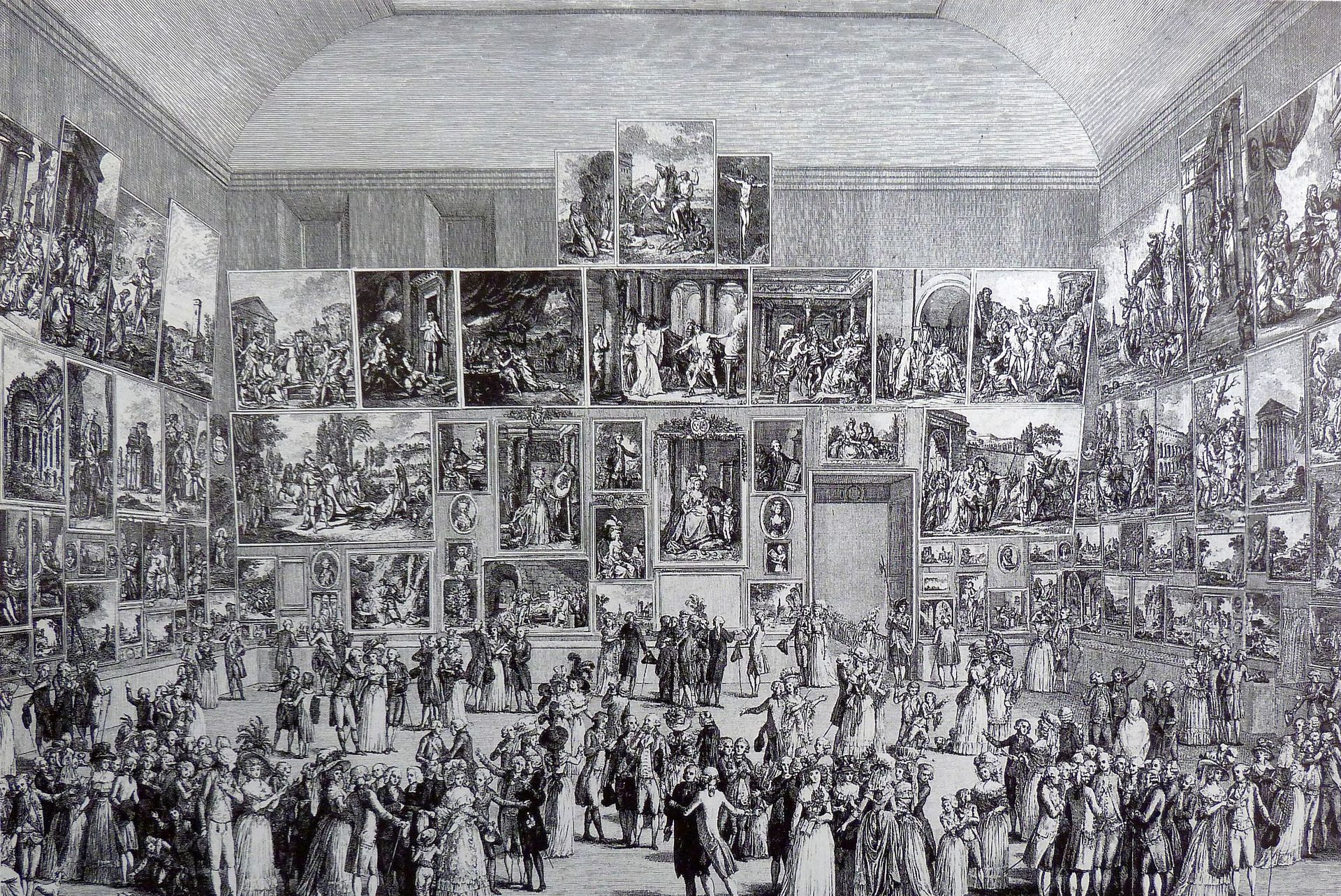

Academies and Salons: central institutions. The Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture fixed the hierarchy of genres (history painting supreme). The Paris Salon, open to the public, became a social theater where works were judged by critics, elites, and people — the birthplace of modern art criticism (Diderot).

Patronage and Power:

Under Louis XIV, art served as monarchical propaganda. Versailles was the “staging of absolute power.”

In the 18th century, the French Revolution and Napoleon appropriated Neoclassicism: David painted Roman heroes, Napoleon posed as Caesar. Art became a tool of civic and military mobilization.

Museums and Public Spaces: art became a common good. The British Museum (1753) and the Louvre (1793) opened to the public, affirming a new democratic vision of heritage. Libraries and public gardens reinforced this diffusion.

Grand Tour: the initiatory journey through Italy and Greece. Young nobles and artists copied antique statues, brought back sketches and casts, spreading a European taste for Antiquity.

Civic Function: Neoclassical canvases exalted virtue (Horatii, Brutus); public monuments became “republican temples” (the Panthéon). Art was meant to educate, inspire, and elevate the community.

👉 With Classicism and Neoclassicism, art crossed a new threshold: no longer the preserve of elites or religion, it became a civic, educational, and universal tool, open to public judgment and dedicated to shaping consciences.

5. Emblematic Works

1.The Louvre (1660–1700, Paris)

Originally a royal palace, it became the great manifesto of French classicism with Perrault's Colonnade: a regular façade, perfect balance of ancient orders, and sober monumentality. Transformed into a museum in 1793, following the Revolution, it inaugurated a new era: art became public property, offered to all citizens and no longer reserved for the elites.

2.Nicolas Poussin –The Shepherds of Arcadia(1637–1638)

A masterpiece of pictorial classicism. In a perfectly ordered composition, Poussin depicts shepherds meditating on the inscription “Et in Arcadia ego” (“I too am in Arcadia”), a reminder of death even in an ideal world. The balance of forms, the rigor of the composition, and the moral depth make it a painting that is both poetic and philosophical.

3.Jacques-Louis David –The Oath of the Horatii(1784)

An icon of neoclassicism and a manifesto painting of the Enlightenment. Three Roman brothers swear to defend their homeland under paternal authority. Rigid lines, clarity of colors, theatrical gestures: everything exalts civic virtue, sacrifice for the common good, and republican rigor. This work will directly influence the imagination of the French Revolution.

4.Panthéon of Paris (1757–1790, Soufflot)

Inspired by the Roman Pantheon, this neoclassical temple combines geometric purity and solemn monumentality. Initially designed as the Church of Sainte-Geneviève, it became a republican sanctuary after the Revolution, welcoming the “great men” of the nation. A symbol of architecture serving collective memory and the republican ideal.

5.Antonio Canova –Psyche Revived by the Kiss of Love(1787–1793)

A marble sculpture of controlled sensuality, it illustrates neoclassical grace: fluid drapery, perfect balance of bodies, contained emotion. The moment frozen between life and death, fragility and love, embodies the moral nobility and ideal beauty that Winckelmann described as “noble simplicity and quiet grandeur.”

6. Heritage and Legacy

Classical and Neoclassical art left a lasting, structuring mark on European and global culture.

Institutionalization of Art: Academies codified rules; museums (Louvre, British Museum) became civic temples. Art education, until the 19th century, rested on drawing, Antique study, and the hierarchy of genres.

Architecture and Urbanism: Classical vocabulary (colonnades, pediments, domes) became the official language of public buildings.

In Europe: Arc de Triomphe (Paris), Neue Wache and Altes Museum (Berlin, Schinkel), Saint Petersburg (Rossi), London (John Soane).

In the US: Capitol, White House, Jefferson Memorial — republican filiation with Rome.

Empire Style and Global Spread: Under Napoleon, the Empire style (eagles, laurels, palmettes) dominated furniture, metalwork, urban design, spreading from Paris to Milan, Warsaw, St. Petersburg.

Dialogue with Romanticism: In the 19th century, Neoclassicism was criticized as cold, too rational. Romantics (Delacroix, Goya, Turner) opposed passion and the sublime to Classical rigor. Yet this dialectic shaped modernity: rational Classicism and emotional Romanticism remained Europe’s twin legacies.

Posterity: Until the 20th century, courthouses, parliaments, libraries, and museums bore Neoclassical ornament. Today, Classical monumentality still conveys stability, dignity, and permanence.

👉 Classical and Neoclassical art gave Europe its universal vocabulary of greatness — a heritage our cities, institutions, and symbols continue to embody.

7. Imperion – Heir to Clarity

Imperion does not copy Antiquity: we extend its measure and light.

Our creations are guided by proportion, symmetry, and harmony.

We borrow antique symbols (laurel, palmette, medallion) not as frozen past, but as a universal language of excellence.

Like Classicism, we believe in a beauty that instructs and uplifts; like Neoclassicism, we want art to be heroic, moral, timeless.

✨ To inherit Classical and Neoclassical art, for Imperion, is to affirm that beauty is not ornament but a clear voice that orders, elevates, and unites.